An Epic 29-Hour Leap Day on the Cesar-Comici Route

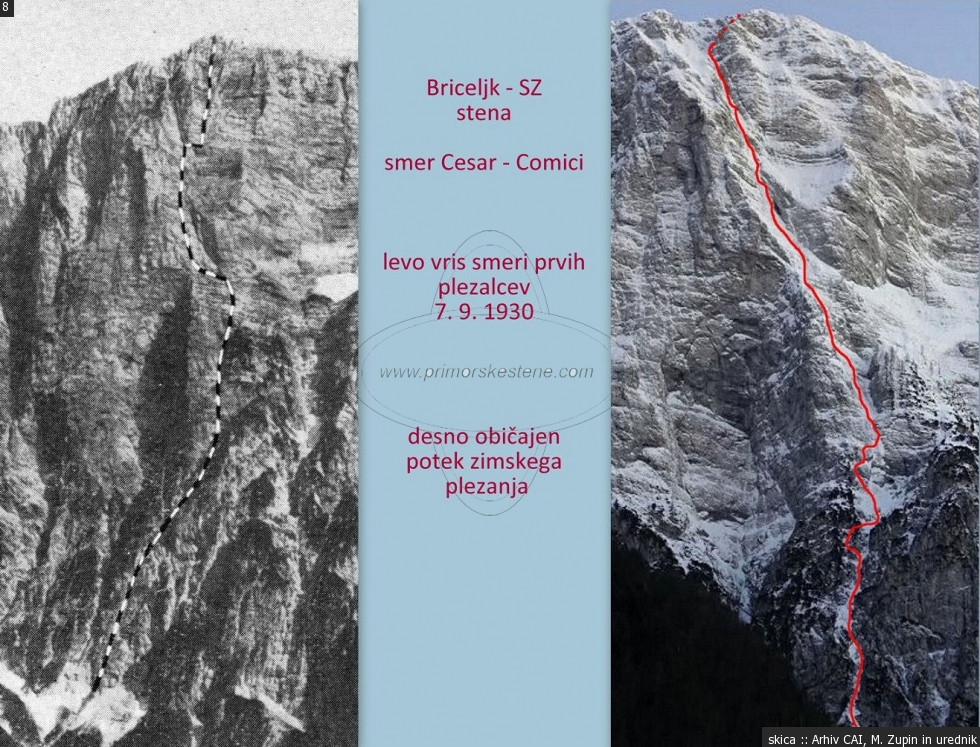

On February 29, 2020 (the leap day), Milivoj Bučan and I did a winter ascent of a 1300 m long Cesar-Comici (IV+/4+) route on the widest (7 km wide) and one of the tallest barriers in the Julian Alps, Loška stena (stena meaning "the wall" in Slovenian). The route holds historical significance, as it was first climbed by Emilio Comici and Jože Cesar on September 7, 1930.

This post is based on the climb report I wrote in Slovenian on the aopdng.si blog after the ascent in 2020, a few weeks before the Covid-19 lifestyle took over the world.

Our story

The approaching spring has begun to trigger feelings of disappointment as I did not climb a single longer winter route. The information about the excellent conditions on the Cesar-Comici route on the giant face of Loška Stena puzzled me every day, as it is probably the most striking line on the longest barrier in the Julian Alps. I had admired Loška Stena with awe since I started at the alpine school when, after the first ice climbing practice, it hung above us, tiny beginners, with its majesty all lit up by the setting sun.

A few days after hearing about the perfect conditions on the route, my friend Milivoj and I started to think more seriously about going for it. Milivoj had been observing the line for years, but this was a rare occasion when the whole route would be in top conditions. The only possible day for the climb was Saturday, 29 February, as a weather turn with snow was forecast for Sunday. But this added to the tension before the climb because we knew very well that we had to climb the route in a single day.

We left our hometown Nova Gorica a little after 4 am and were at the foot of the wall at 7:30. I didn't know exactly what to think when I looked up at such a massive over our heads; at times, it seemed that we would be immediately on top of it, but deep down, I knew that this was far from the case.

The perfect conditions started right at the start and got worse only on one short overhang, less than 100 m higher. We were practically running over the lower part, and the slope didn't give way enough for me to stretch my legs and relax my calves for a moment.

The weather was cloudy at first, but about halfway up, the clouds were joined by the wind, which blew annoying spray avalanches over us. They followed us all along the route, most often landing on our heads just as we were in the middle of a crux.

Until about halfway up the route, we followed the snow band in excellent conditions. At a larger hole in the second part of the route, we had a snack and took a few minutes to rest. Up to this point, we climbed unroped without any major problems, but it was already taking its toll on our minds. At the first steeper step directly out from the hole, the thaw had already caused the ice to break away from the rocks, so we decided to look for a safer passage on the left side. First came a delicate, airy traverse on the thin ice, where I wondered whether I was more uncomfortable looking down into the 800 meters of the abyss just below my crampons or looking up at the very distant rim of the wall.

At the traverse, I went too far left and got trapped, so I had to get the rope out of my pack and quasi-rappel (downclimb) a few meters on a single piton. This maneuver took us some precious time. Fortunately, we found nice passages over steep rock slabs with compact snow and soon reached the last vertical step, where we built an anchor on ice screws and made our first belay of the day. The ice hook again proved to be an indispensable piece of protection equipment for such mixed conditions (rock, snow, ice, and frozen turf). Above the step, the wall got less steep, so we paused momentarily and continued to the top. About 100 meters below the summit, we turned on the headlamps, which were later spotted by a fireman from the valley, who informed the local search and rescue guys, as two lights so high up on the mountain seem unusual at this time.

I was a bit relieved after coming out from the vertical world, as I thought that the hard work was behind us and all that was left for us was a safe, albeit long, walk into the valley. Luckily the weather cooperated, and the views stretched far into the warmly lit villages of the Italian Po Valley. However, an eerie wind kept hinting that an epic adventure was about to start.

The climbing went pretty smoothly, but I can't say the same about the descent. I'll begin in the snow cave just at the top of Mount Briceljk, into which I almost fell after the first few steps from where the route exited. The cave reached down to the grassy ground and was just big enough for two people. It offered complete shelter and silence, and the air quickly warmed up to a comfortable temperature, so we were already thinking about wrapping ourselves in space blankets and spending the night there. Fortunately, we realized that the idea of a bivouac was only supported by fatigue and that the approaching weather made it a very unwise idea, so we packed up our gear, had a few snacks, and stepped out into the freezing, windy night.

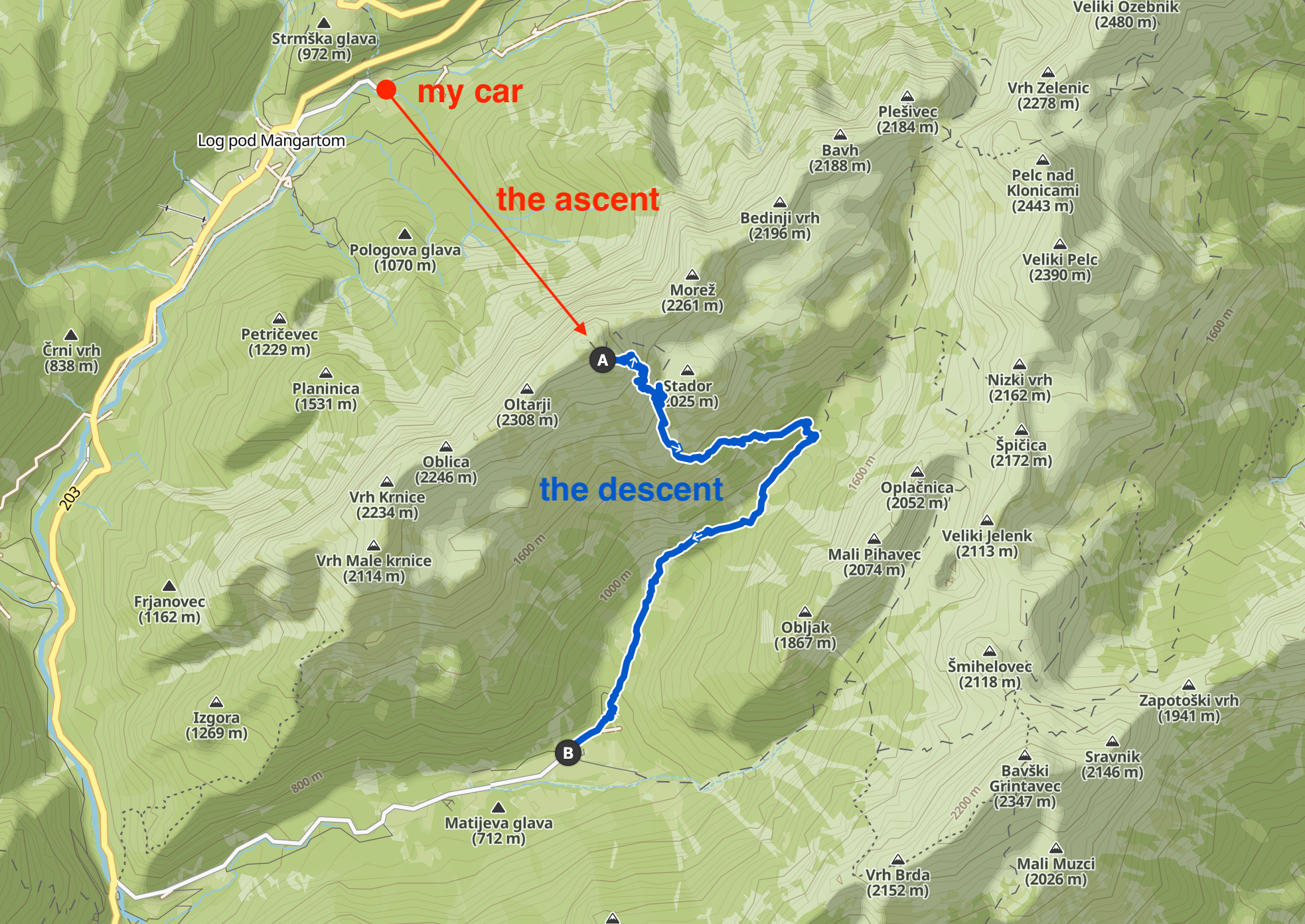

The wind constantly swirled snowflakes around us, reflecting precious light from headlamps and shamelessly interfering with visibility and spatial orientation. Due to fatigue and low visibility, we mistakenly thought we were standing on the ridge separating the valleys Loška Koritnica and Bavšica, so we kept to the right side of the ridge instead of descending to the left, where the real trail was, blatantly ignoring the map on my Garmin Fenix 6, which showed the right way. The slope turned into a wide gully and kept getting steeper and steeper. We hesitated for a while, looking for the right trail, but when the calendar turned to March, we decided that all we needed to do was head straight down toward the valley. What followed was six full rappels and a lot of downclimbing, where the already destroyed calve muscles were tearing even further. Finding the right spots for building solid rappel anchors required a lot of effort and improvisation. The rappels were psychologically exhausting, as each time we descended into unknown, dark depths, wrapped in a cloud of wild, illuminated snowflakes. During the second-to-last rappel, I suddenly realized that the mist around us had taken on a blue shade, signaling the awakening of a new day. During the rappel, the mist cleared up momentarily, revealing a gentle slope leading into the woods not far below my feet. We had one more rappel to make before reaching safe ground, which we made on the last remaining piton and an ice hook shoved into chossy rock.

The only thing left to do was a 2-hour walk in the snow to the road at the end of the valley. At first, the walk was tolerable, but later, when the snowflakes turned into cold raindrops, it became very annoying. During our descending marathon, both Milivoj and I experienced a few minor hallucinations due to fatigue. Milivoj saw a pair of skiers in the middle of the night in one of the most remote valleys in Slovenia, while I kept falsely hearing him talking to me the entire walk down the valley and I kept asking him to repeat himself. During the last part of the walk, we heard a few avalanches due to the new snowfall, which reminded us that spending the night in the snow cave would have become a much more dangerous adventure.

We hadn't yet thought about a concrete plan for getting out of the Bavšica Valley and to my car in Log pod Mangartom, and we were still without a phone reception that would allow us to call a local friend we knew to give us a ride to the 10+ km distant car.

As we approached the parking lot in Bavšica at 11:30, soaked to the bone, we saw a white van and a person there, which was unexpected in such a remote valley on a rainy day. In order to catch them before they went about their business, I started to run towards them. As I got closer, I saw a lady in a sky-blue North Face jacket coming toward me and she asked me if I was Alex. It turned out that Mili's partner Polona had called her friends from Log, Urška and Robi, who had been waiting for us for a couple of hours. That was the most comforting surprise we could get after 29 hours of discomfort. Then they drove us to my car, offered us a hot meal and dried our clothes to warm us up to regain some of our energy for the drive home.

The climbing on this great, historic route was outstanding, and the cohesive teamwork with which we overcame all the difficulties along the way, especially on the descent, made this one of the most memorable adventures I have ever had in the mountains. The price we paid were slightly frostbitten fingers, which caused an annoying loss of the sense of touch in our fingertips for the next few weeks.

The next day Milivoj noticed his backpack was missing. Robi went to look for it in the parking lot, where all he saw was a pile of snow with the missing backpack underneath. Since the Covid lockdown started a week or two later, he did not get his backpack until a few months later.